The Surprising Truth About American Bilingualism: What the Data Tells Us

We Americans think we suck at languages. We particularly think we suck when compared with European countries, “where everybody speaks three or four languages.” Yet this view of our country is outdated. The surprising truth is that the United States is a world leader in bilingualism.

This truth matters because the skills that American bilinguals possess not only help those individuals advance in their careers, but taken together, American bilinguals are key to building American soft power.

By bilingual, I mean someone who actually uses two or more languages on a daily basis. It’s not the only definition, but it’s the one many scholars prefer because it’s so useful. Here’s why:

First, what has been called the “bilingual breakthrough,” generally referring to being more receptive to different perspectives, happens with the command of a second language. Most of the advantages of being bilingual, including a delay in the onset of symptoms of dementia, seem to accrue upon gaining command of one language beyond your native tongue. Additional languages may be icing on the cake, but two languages are what it seems to take to bake the cake.

Second, using your other language on a daily basis means that you are getting the most out of being bilingual. Otherwise, it’s like knowing how to play the piano without actually playing it. And by using your second language for part of every day, you are constantly improving your skill — using it, not losing it.

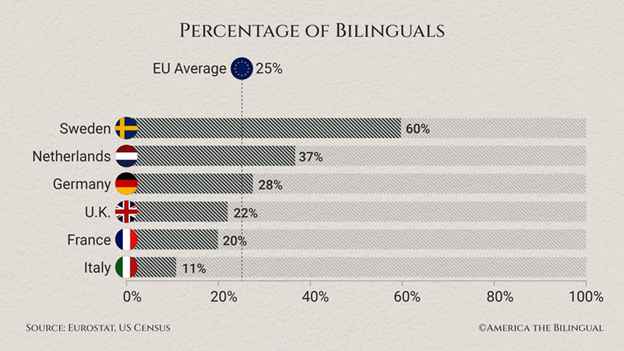

The data might surprise you

Do these percentages seem lower than you expect? It might be due to an availability bias.

Sweden´s higher percentage is what we might expect for one of the Scandinavian countries, where it seems that every Swede we’ve met speaks English. Yet overall, only about 60% of Swedes use a second language every day. The fact is, many Swedes speak only Swedish because it’s all they need in their daily lives.

France, at 20%, may seem low to Americans who have visited Paris and other French tourist destinations, but Americans who have traveled into the French countryside often find a different linguistic reality, as will those who travel the countryside throughout Europe.

When we think that “all Europeans speak three or four languages,” our judgment is likely influenced by availability bias, where we color our perceptions to match the experiences we most readily remember. To get a sense of this, consider a bilingual European you know. If you met them while they were living in the US, you are not drawing a random sample from the population. Most people don’t live outside their home country; only 3.5% of the global population does so.

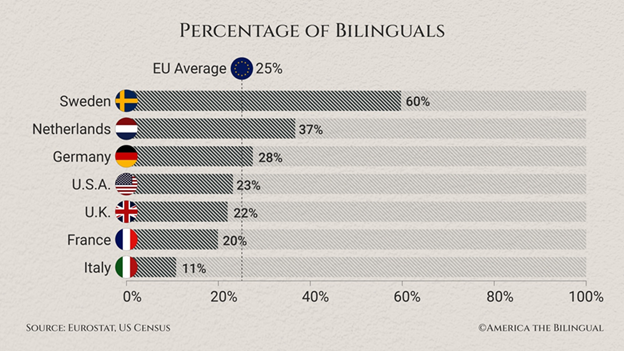

Now let’s insert the US percentage into this visual.

The US bilingual percentage is near the middle of the EU pack.

Did it surprise you to find it in the fourth position?

At 23% bilingual, the US falls near the middle of the pack, not far below the EU average of 25%. We’re in the ballpark for European nations in terms of the percentage of our population that uses a second language every day.

It may seem to some that 23% is high, but that may again be availability bias, because most American bilinguals speak their second language at home, not in public.

American bilinguals are hiding in plain sight, or better said, hiding in plain speech.

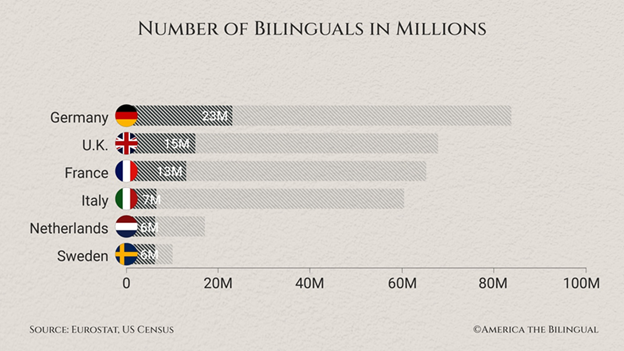

Looking at the data another way

Percentage is one way to look at bilingualism, but we can also look at the actual number of bilinguals — that is, people rather than percentages. Here’s how those same European nations stack up:

Showing people rather than percentages results in a different perspective.

The dark gray bars show the number of bilinguals, while the light gray bars show the total population. Sweden has moved from the top to the bottom. Even though it has the largest percentage of bilinguals, at 60%, it is tied with the Netherlands for the smallest number of bilinguals, at 6 million, since its total population is only 10 million.

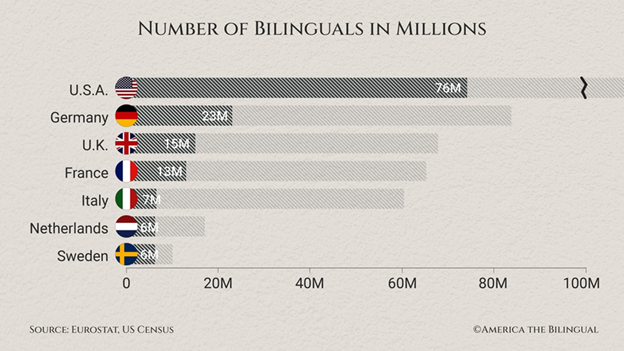

Now let’s insert the US into this visual:

The US has far more bilinguals than any EU nation, three times as many as second-ranked Germany, and five times that of France.

The US is in the first position, and by a wide margin. With a population of about 331 million, the US is much larger than the largest EU country, which is Germany. In fact, we would need four slides at this scale placed side-by-side to show the true size of the US population.

The result of being 23% bilingual means that we have about 76 million bilinguals. This figure is three times the number of the nearest EU competitor.

The US takes the gold

How can Americans suck at languages if we have far more bilinguals than any EU country?

The answer is, we don’t. Size matters.

Think of the Olympics. The Olympic Games are not a contest of the average fitness of a nation, but rather, the performance of elite athletes from that nation. While certain countries have advantages because of their unique sporting cultures, overall it is the largest nations that win the most medals because they draw from the largest pools of candidates.

Percent bilingual is like the average fitness level, whereas the number of bilinguals is the pool from which top linguistic actors emerge.

Does the whole world speak English?

But do English speakers even need another language today? We often hear that “the whole world speaks English,” and it’s true that in the world’s top tourist destinations, you can get by with English. You can also usually get by with English if you’re buying things. But there is a saying: “If you want to buy something, you can do it in your language. If you want to sell something, you better do it in theirs.” This holds not just for selling cars and ketchup, but for selling ideas.

Whether you are working overseas in development, health care, or education, in diplomacy or in the military, your success depends on your ability to work well with colleagues in that country and to be persuasive. You must build relationships. Trying to build relationships overseas and be persuasive while speaking only English is like going to a cocktail party with a bag over your head.

Our various American bilinguals, by contrast, can be the life of that party. They can operate professionally around the world — in the largest countries, and in many of the smallest ones, too. Speaking a language well means you understand cultural references and different points of view. American bilinguals are the people who, far more than our few elected officials, build American soft power every day, all over the planet, simply because there are so many of them.

America’s secret sauce has many savory ingredients

Understanding the sheer quantity of our bilinguals is the start of understanding American bilingualism. But our large overall size is just the beginning.

Several nations have more absolute linguistic diversity than the United States. Countries like Papua New Guinea and Nigeria, for example, can boast of having many hundreds of different languages that are spoken. But most of these languages have a small number of native speakers who use them primarily within the borders of those nations.

No nation has more speakers of the world’s most-spoken languages than the US, because no nation has more immigrants than the US. This is our secret sauce, and our sustaining strength.

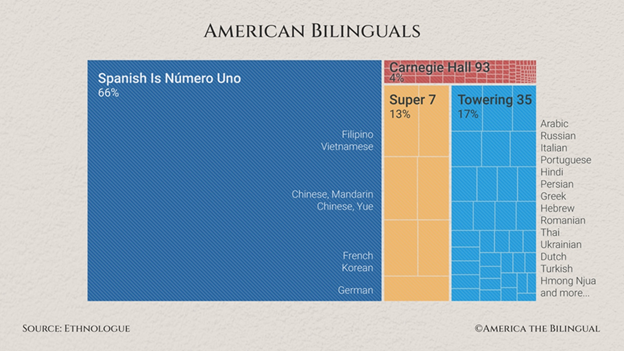

The US is unmatched in the breadth and depth of the languages Americans speak in addition to English. We can get a sense of this from the following visual:

English-Spanish bilinguals comprise two-thirds of American bilinguals. The ‘Super 7’ bilinguals, with more than one million speakers each, constitute 13% of our bilingual population. Other languages with at least 100,000 speakers constitute 17%, the ‘Towering 35.’ The ‘Carnegie Hall’ languages, with a minimum of 3,000 bilinguals, number 93 languages. (The hall’s seating capacity is 3,000.)

It will come as no surprise that English-Spanish bilinguals account for the largest group of American bilinguals. Fully two-thirds of American bilinguals speak Spanish as their other language. This is because most immigrants have come from Latin America, and also because the American Southwest was part of Spanish-speaking Mexico until the mid-nineteenth century. The Spanish language has always been woven tightly into our American tapestry, as reflected in many of our place names — from Florida and California to Montana and Rio Grande.

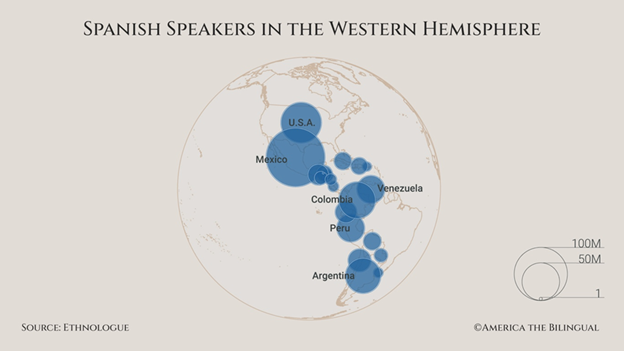

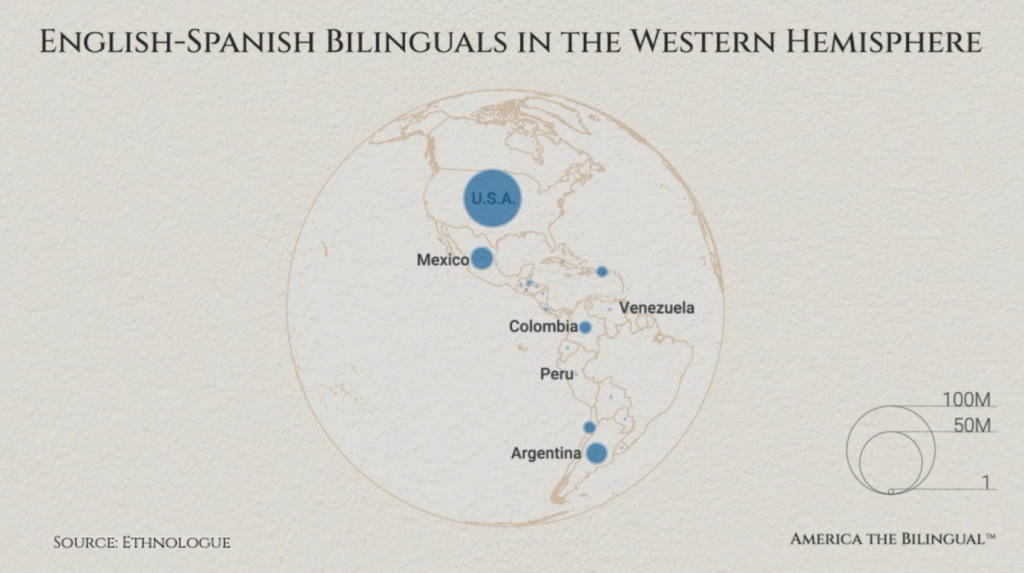

The only country that has significantly more Spanish speakers than the US is Mexico, as seen in this bubble graph:

Only Mexico has significantly more Spanish speakers than the US. Spain (not shown) has a comparable number as the US.

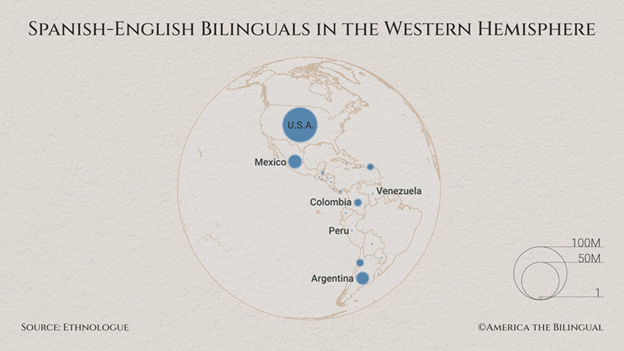

Moreover, as shown in the second bubble graph, the US has more English-Spanish bilinguals than all of Latin America combined.

The US has more English-Spanish bilinguals than the rest of Latin America combined.

These Americans have the linguistic skills to operate professionally in most of the Western Hemisphere, as we see in the next visual. We also have nearly one million English-Portuguese bilinguals, who fill in Brazil on this map, and with it, the rest of the Western Hemisphere.

English-Spanish bilinguals are comfortable working in nearly all of the Western Hemisphere. Portuguese-speaking Brazil is the only exception.

But the size of our Latino bilingual population is only the most obvious feature of our American linguistic landscape. There is much more to the story.

The Super 7

We have seven other languages with more than one million speakers each. At our America the Bilingual Project, we refer to these languages besides English and Spanish as our Super 7.

These seven (shown in the gold rectangle) include two languages that have a long history in North America, being well established even before our nation was born — namely, French and German. But what is a surprise to many is that the remaining five giants are Asian languages, with most of their growth coming in the last 50 years. These are Tagalog (Filipino), Vietnamese, Mandarin Chinese, Yue Chinese (Cantonese), and Korean.

There is a danger when tossing around big numbers that their true significance is lost, so I should emphasize that when it comes to languages, one million speakers is a huge number. The average number of speakers for America’s Super 7 languages is 1.3 million, which is a population fully sufficient to have those languages flourishing in a bilingual environment. (Consider that Iceland has a population of only 373,000 which is more than enough to allow Icelandic to flourish despite the fact that most Icelanders also speak at least some English.)

These Super 7 languages are also giant world languages outside of the US (which is not the case for our friendly Icelanders). All this is to say that American bilinguals of the Super 7 languages have ample opportunity to sustain their language skills and to operate professionally across the planet, and millions are doing just that.

The Towering 35

Continuing to our next weight class, we can look at languages spoken by at least 100,000 Americans and as many as one million. The American bilinguals in this group of languages, which we call the Towering 35, average some 337,000 and comprise 17% of American bilinguals (shown in turquoise in the visual). These include languages with close to one million speakers, among them Portuguese, Hindi, Arabic, Russian, and Italian, as well as those at the lower numeric end of this group, where we find such linguistically diverse languages as Persian (Farsi), Greek, Hebrew, Romanian, Thai, Ukrainian, and Dutch.

The Carnegie Hall 93

Finally, we can look — with some awe — at the remaining 4% of American bilinguals, whose languages have fewer than 100,000 speakers but at least 3,000, which is the seating capacity of that historic American concert and lecture venue, Carnegie Hall. There are 93 languages in this small but mighty class. These include Native American languages such as Hawaiian, Hopi, and Chippewa; languages with close to 100,000 speakers, such as Napali, Swahili, and Hungarian; and island languages, where we find Marshallese, Figian (Fiji), and Icelandic. The average number of speakers for these 93 languages is 26,000.

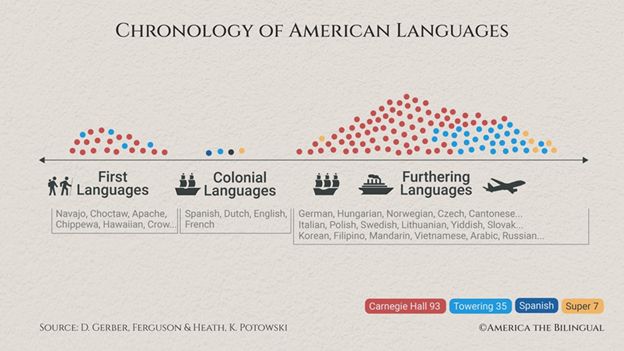

The combination of so many world languages spoken by such large numbers of people is uniquely American, and relatively recent in its manifestation. How did it happen?

Immigration reform, circa 1965

The Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 (also known as the Hart-Celler Act in honor of the two congressmen who sponsored the bill) passed the House and the Senate by overwhelming, bipartisan majorities. President Lyndon Johnson signed it into law at a ceremony held at the foot of the Statue of Liberty.

Prior immigration laws favored Europeans in proportion to the Europeans who were already here. The 1965 law, in contrast, was open to all nationalities and races. It emphasized family reunification and refugee status. It welcomed professionals, artists and scientists, as well as skilled and unskilled workers in occupations with an insufficient labor supply. It opened the US to its third major wave of immigration, which we are still surfing today.

What were the prior major waves of US immigration? The first hit our shores in the mid-1800s, when Europeans came in sailing ships. The second wave happened between 1875 and the outbreak of World War I, when more Europeans came, mostly in steamships.

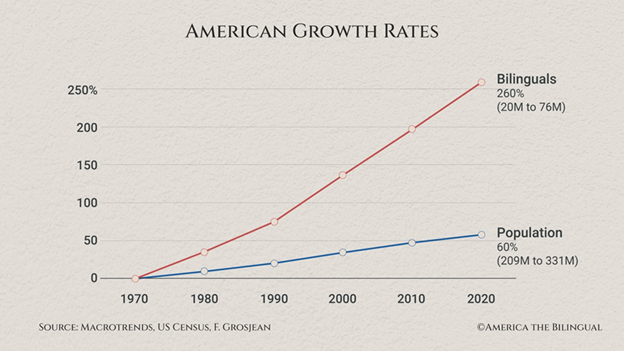

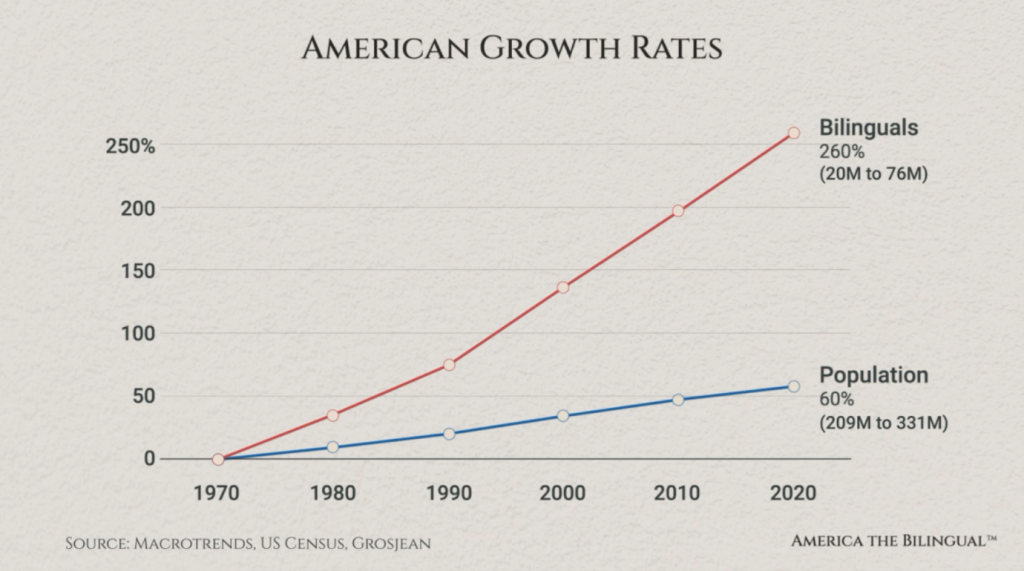

The 1965 law, which went into effect in 1968, increased the number of immigrants, gradually at first, and then dramatically, as this visual illustrates:

The US bilingual population has grown four times faster than the overall population due to immigration, together with changing attitudes about the benefits of bilingualism.

The Hart-Celler Act explains part of the steep rise in American bilingualism, but not all. In the past 50 years there have also been profound changes in attitudes toward bilingualism.

Shifting attitudes away from monolingualism

Up until the mid-twentieth century, American immigrants lost their heritage languages at record speed compared with immigrants to other countries. Grandchildren of immigrants, and sometimes even the children, became English monolinguals in short order. It was an era when there was ample social pressure for immigrant families to fit in and be able to speak English as well as the neighbors next door, and such social pressure has continued. But much of the language loss prior to 1960 was the result of simple practicalities.

Most American jobs before 1960 were at companies doing business locally, regionally or nationally. These jobs required English, and few positions required languages other than English. In the family domain, return trips to the home country entailed considerable time and expense to sail or steam across an ocean; most of the immigrants had little time or money. Communication technology consisted of the handwritten letters sent through national postal systems, which took weeks if not months to be delivered.

But as the second half of the twentieth century unfolded, the situation changed dramatically. Airliners replaced steamships, and employment opportunities became increasingly international, even at medium- and small-sized enterprises.

Meanwhile, communication technology passed through repeated revolutions, culminating in the ubiquitous, nearly free, live video communication we enjoy today.

Occurring during these same years were big changes in applied linguistics. Researchers demonstrated that the early studies suggesting that monolingual education was superior to bilingual education got things exactly wrong. Rather, it was the bilingual students, particularly if they were taught in two languages, who consistently outperformed their monolingual peers. This science, as well as other research indicating the likely mental health benefits of bilingualism, made big news around the world.

Rather suddenly, parents, teachers, and students themselves realized that young Americans would have brighter futures if they were bilingual and biliterate. At the same time, becoming and remaining bilingual became far more practical. Of course, American children must speak English perfectly, but this in no way interferes with them also being able to communicate well in a second language. When that second is also their home language, family harmony improves, while better career opportunities beckon.

Linguistic diversity on the North American continent, always large, blossomed in the last half century due to immigration and changing attitudes that view English bilingualism as both practical and beneficial.

The American linguistic landscape, unique in its breadth and depth, is reflected in another indicator we call second-home languages. For example, the only country that has more Japanese speakers than the US is Japan. The only country that has more Vietnamese speakers than the US is Vietnam. You can say the same thing for more than a score of other languages where the US is their second home.

Prior to 1960, when US immigrants saw no practical means, nor any particular benefit, to retaining their heritage languages, there was some truth in saying “America is where languages go to die.” Today it is more accurate to say “America is where languages come to live.”

It’s also true that not all American bilinguals are the result of recent immigration. An estimated 10%, approximately seven million American bilinguals, grew up in English-speaking homes but managed to gain professional competence in a second language. Improvements in teaching, study abroad opportunities, and communication technology have made second-language acquisition more accessible than ever.

Welcome to America the Bilingual

In two generations, America has transformed itself from a monolingual mouse to a linguistic lion. This brings benefits not only to the individuals who can lead more rewarding lives, but also to our nation as it builds its soft power day by day, person by person.

Yet, if we have 76 million bilinguals, we also have the complement, or some 250 million monolinguals. This figure also leads the world, and within that quarter billion lies both risk and opportunity.

One of the risks of being 74% monolingual — in English — is that this situation feels so utterly normal to most Americans. American parents can be lulled into complacency, believing that English is all their children will need. But if their children wish to enter a global workforce in a professional capacity, they will be at a disadvantage as English monolinguals. These children also risk missing out on one of life’s great adventures and lifelong learning opportunities that bilingualism opens.

The opportunity, on the other hand, lies in the millions of monolingual English adults who recognize the benefits that both they and their children can gain by adding a language. This recognition is reflected in the growing market for adult language learning, and in a demand for dual-language schools that far outstrips the supply.

Given the size of our monolingual population, we have the greatest opportunity to continue to transform ourselves from a majority monolingual nation to a majority bilingual one. No other nation has the resources in education, technology, and most of all, other Americans, who can sit down and have a chat with a learner of another language. Name a language and chances are you can find an American nearby who can help you learn it.

There is another opportunity, not for Americans to help themselves directly, but to help the world.

While the whole world does not speak English, more than a billion people badly want to. The US contains the world’s largest repository of native English speakers who can help. Learners can often find technology and classes. But what is terribly difficult to find are opportunities to have genuine conversations with native speakers. Americans taken together have the greatest opportunity to help the world’s English learners, while making friends with people we would otherwise not likely meet. This is no small thing.

Bilingualism has always been about more than just understanding another language. Bilingualism is about building relationships, and relationships are what fosters peace.

America, already a world leader in bilingualism, is just beginning its bilingual century. Americans, and the world as a whole, will be better because of it.

No matter where you may be in your own bilingual journey — even if you have just begun — you have the opportunity to continue your adventure, to build your bilingual powers, and help others do the same.

—Steve Leveen, Founder, America the Bilingual Project

You can book Steve for many different audiences

You can book Steve for many different audiences

First, know that she has one of those glorious English accents (or what all of us who are not English would call an accent), which makes her a natural for the audio book narration that she does. Although U.S. born, Caroline grew up in England and studied literature at the University of Warwick (fyi for American ears: that second “w” is silent).

First, know that she has one of those glorious English accents (or what all of us who are not English would call an accent), which makes her a natural for the audio book narration that she does. Although U.S. born, Caroline grew up in England and studied literature at the University of Warwick (fyi for American ears: that second “w” is silent).

Leave A Comment