25. Dual-Language Education, Report #2:

Winds of Change

In this second episode on the dual-language movement, we hear from six voices of change in America. They trace their heritages to different countries and have had different life experiences, but they share a common vision for America. They would move our old melting pot respectfully to a museum of American history. In its place, they would welcome all Americans to step up onto a launch pad constructed of English and reinforced with bilingualism.

It’s not that melting together—or at least coming together—is completely wrong. I endorse the binding ties of English to help bring Americans together with one another, and with so much of the world, which is full of English-language learners.

As with so many things in life, it’s a balance.

THE IMMIGRANT INSIDE

“I was born in Southern California and raised there. When I started first grade, that was the first year that desegregation occurred in the school system, so from the very beginning of my educational career, I have had a great opportunity to have very diverse students alongside me.”

That’s Kris Nicholls, head of professional development for the California Association of Bilingual Education (CABE).

“People look at me and they say, ‘Well, she’s Caucasian.’ Okay, I am, but they don’t understand that you have to look deeper than that.” In the episode, we hear how Kris, as a daughter of an immigrant, has herself felt the sting of prejudice.

“I would say that one of the things that has really been pivotal in me being able to be as successful as I am as a person, as a citizen, as an educator, as a parent, in all aspects of my life, has been this journey that I’ve taken to become bilingual.”

For Kris, bilingualism is not just a key to individual success, but to the success of our country. “This idea of what America is—recognizing and celebrating each other’s languages, cultures, and just who we are as individuals, that we all can be Americans without having to give that up.”

Her advice to parents: “Be an advocate for your child to have this opportunity.” And a good place to start, she says, is the Dual Language Schools.org website.

Kris’s mother and father early in their marriage. She was the daughter of Irish immigrants to Canada who later immigrated to California, where Kris was born.

Kris with her family today. People look at her, she says, and see simply a Caucasian. “You have to look deeper than that,” Kris says.

GOLD, DOWN VALLEY FROM ASPEN

“There was a time when it wasn’t a big interest and then I would say about 10 years ago the trajectory just went straight off the charts—we had so many families wanting dual-language education.” That’s Suzanne Wheeler-Del Piccolo, principal of Basalt Elementary School in Basalt, Colorado.

The reason, she believes, was a meeting of minds. “I think our community came to really understand that we were a dual-language community and being bilingual, biliterate was an asset to the work world. Both Anglo and Latino families saw that as an asset.”

But it wasn’t easy. It was hugely challenging to find enough teachers and then find them an affordable place to live so close to exclusive Aspen. We hear how, with some creativity and grit, the community made it happen.

“I really believe our future is based on an educated populace,” says Suzanne. Dual-language schools have the power to make students feel they belong. “I have great hope for this country.”

FREEDOM FIGHTER

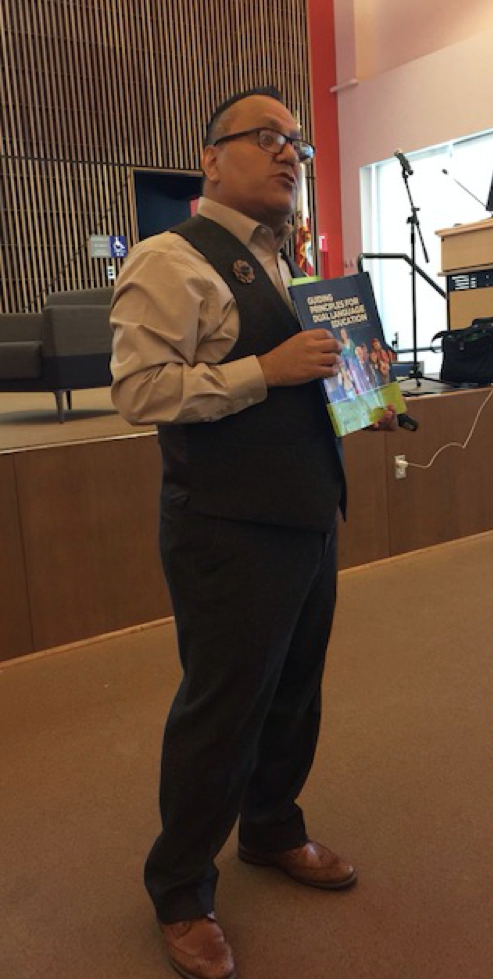

“Social justice is at the very heart of the dual-language movement,” says Tony Báez, addressing the two thousand bilingual educators during his keynote at the La Cosecha (“The Harvest”) conference in Albuquerque last November.

Tony is a director of the Milwaukee school board and has been a teacher and an administrator, a professor and a dean. For him, the dual-language movement goes way beyond learning how to speak two languages. It provides “a learning that is transformative in that it creates a next generation of kids that are not only bilingual, bicultural, but better human beings.”

The grassroots nature of the movement is what gives it the power to address segregation and bring communities together.

“We need to grow the idea of dual language to the point that everybody in this country accepts the notion that bilingualism is good for everybody.”

“Social justice is at the very heart of the dual-language movement,” says Tony Báez, above, during his keynote address to bilingual educators last November in Albuquerque, and below, during his interview with Steve.

ONLY WHEN WE ARE UNCOMFORTABLE

José Medina believes dual-language teachers must not only be excellent teachers but must also “embrace our role as defenders of equity and social justice.”

José Medina was the director of dual-language and bilingual education at the Center for Applied Linguistics before launching his dual-language educational consulting company. At La Cosecha, he led a large and lively workshop in which he occasionally made the audience uncomfortable with tough questions about their roles in fostering change. “Only when we’re uncomfortable do we actually grow,” he says.

His own family background informs his view of his work. “Some of my family members were not able to achieve at high levels academically in English or Spanish because they weren’t provided native language support,” he says.

José considers the loss of Spanish among American Latinos a sad and avoidable outcome of earlier attitudes and schooling methods. “I can tell you that some of my cousins—and we’re all first-generation Mexican-Americans—don’t know how to speak and communicate in Spanish, even within our own family.”

José recommends a free resource from the Center for Applied Logistics that explains what dual-language programming is and how it has the capacity to “really change our country and move it forward.”

“I would dare to say that if parents fully understood the research behind dual language, that there would be less of the eroding of the culture and language in the home.”

THE FUTURE OF EDUCATION

Steve interviews Fabrice Jaumont at Albertine, New York City’s elegant French bookstore.

“I think bilingual education is a good education. It triggers so many benefits that are so important for communities and schools and cities, and even the country, that it should be everywhere.” Fabrice Jaumont is a former private school director and is currently the Education Attache for the Embassy of France. He is the author of The Bilingual Revolution: The future of education is in two languages.

Says Fabrice, “It’s no longer acceptable to just be grubbing in one language or in one vision of one’s culture or one’s society.”

Fabrice now helps parents lobby their local public schools in Brooklyn to start dual-language programs. He began by sharing a photocopied “road map” created by some parents who had been successful and added to it. “So then I thought, well, it’s been going on for 10 years and I’m getting calls from all over the U.S. now; perhaps it’s time to put this in the book.”

The Bilingual Revolution is an enjoyable read that mixes big-picture ideas with practical advice geared to parents who want to get their own programs started.

One of the parents he writes about is a mother of two young boys who, working with others mothers in Brooklyn, helped create the first Japanese-English dual-language public school in New York City. Her name is Yuli Fisher.

“It felt good because I think we’re all kind of civic-minded and community-minded, and we knew that we were investing in the future of our community,” says Yuli.

“The power of parents should not be underestimated,” says Fabrice Jaumont.

“As I began to look at schools, I found I had a preference for schools that had dual-language programs because speaking a second language has always appealed to me, even though I didn’t actually speak one,” says Yuli Fisher.

“Being bilingual is no longer superfluous nor the privilege of a happy few. Being bilingual is no longer taboo for immigrants who want so dearly for their children to blend seamlessly into their new environment. Being bilingual is the new norm, and it must start with our youngest citizens.” From page 2 of The Bilingual Revolution.

WINDS OF CHANGE

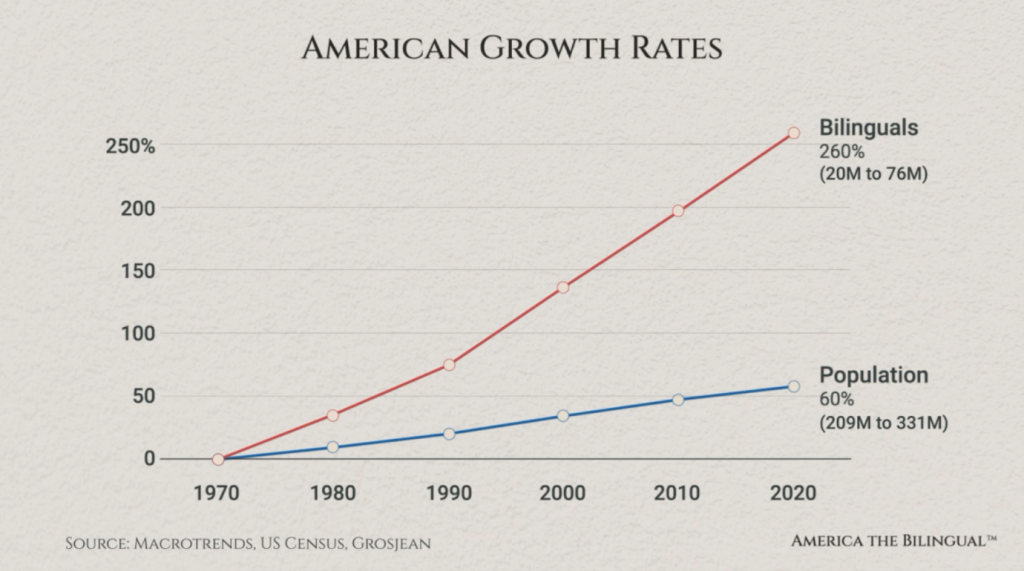

Parents have always wanted something better for their children. Back in the 20th century, “better” meant speaking English with no trace of an accent, and the accepted way to achieve that was to abandon heritage languages. In the 21st century, for an increasing number of people, better is bilingual.

It goes beyond the economic and professional benefits, the mental health benefits. Bilingualism expands to deliver community benefits, including the benefits of being able to see diversity as a strength rather than something to be melted away.

Clearly there are lots of challenges for scaling up dual-language instruction in America, including attracting enough qualified bilingual teachers, and developing materials for all grade levels in multiple languages. But there seems to be so many different parties pulling together—not just immigrant parents, but Anglo parents; not just teachers, but politicians who want the economic advantages of a bilingual workforce for their electorate.

HEAR THE STORY

Hear more of the story in Episode 25 of the America the Bilingual podcast, “Dual-Language Education Report #2: Winds of Change.” Listen on iTunes by clicking here: America the Bilingual by Steve Leveen on iTunes or on SoundCloud here. I’ll let you know about future episodes on Twitter as well.

Sources, Credits and Additional Thanks

We thank David Rogers for his invitation to attend La Cosecha, and Kim Potowski for her continued encouragement and support of America the Bilingual.

The America the Bilingual podcast is part of the Lead with Languages campaign of ACTFL — The American Council on the Teaching of Foreign Languages.

This episode was written by me, Steve Leveen. Our producer is Fernando Hernández, who also does our sound design and mixing, and our associate producer is Beckie Rankin. Our brand and editorial director is Mim Harrison. Graphic arts are created by Carlos Plaza Design Studio.

Music in this episode, “Quasi motion” by Kevin Macleod, was used with a Creative Commons Attribution License. Our thanks to Epidemic Sound for helping us make beautiful music together.

Support for the America the Bilingual project comes from the Levenger Foundation.

You can book Steve for many different audiences

You can book Steve for many different audiences

First, know that she has one of those glorious English accents (or what all of us who are not English would call an accent), which makes her a natural for the audio book narration that she does. Although U.S. born, Caroline grew up in England and studied literature at the University of Warwick (fyi for American ears: that second “w” is silent).

First, know that she has one of those glorious English accents (or what all of us who are not English would call an accent), which makes her a natural for the audio book narration that she does. Although U.S. born, Caroline grew up in England and studied literature at the University of Warwick (fyi for American ears: that second “w” is silent).

Leave A Comment