When America Went to War Against the German Language

Americans do remember World War I, but most of us have forgotten the war within our own borders that took place during those same years.

After burning German textbooks from Baraboo High School, a crowd turns to a man waving an American flag. Baraboo, Wisconsin, 1918. (Library of Congress Prints & Photographs Division.)

It was a war against all things German-American, including the teaching of the German language. Our internal war was so violent, destructive and cruel, that as soon as the war in Europe ended, Americans were quick to sweep what happened under the rug. The lynchings, internment camps, and book burnings are not mentioned in our history textbooks. But on the centenary of that forgotten homeland war, the results linger with us still.

Author Erik Kirschbaum uncovers a dark and nearly forgotten chapter in American history, which is nevertheless woven into our national fabric.

“Why won’t Grandfather speak with me?”

When Erik Kirschbaum was taking German in high school in the 1970s he asked his grandfather to practice speaking with him. A frown appeared on his grandfather’s face. “No!” he snapped. He said he had forgotten German. But when Erik asked his mother, she said his grandfather spoke German perfectly well.

He passed away before Erik would know the reason for his grandfather’s response. Not until Erik went to college and began researching what would become his senior honors thesis did he begin to understand that his grandfather’s silence, was a silence and shame shared by millions of other Americans with a German heritage.

Erik continued studying German in college but, “I still couldn’t carry on any kind of a conversation.” So he decided to spend his junior year on an exchange program in Germany. Neither his father nor his grandfather had even returned to the homeland.

Before Erik went, he was warned by a former student that the Americans on the program in Freiburg tended to hang out together and that if he really wanted to learn German, he would have to get away from the pack. Erik did, he says, “by hitchhiking around Germany, mostly on my own, every weekend. Hitching to Bonn, Munich, London or even West Berlin. That’s probably where I learned a good amount of German in that junior year abroad.”

While Jefferson recommended language learning, Adams worried about the dangers. Both men were bilingual. (John David Mann, University of Massachusetts.)

American soil, so fertile for crops, so inhospitable to languages

Hostility toward languages other than English was not a new thing a century ago. At the very birth of our nation, our founding fathers (many of whom were bilinguals themselves) worried about the multitude of tongues spoken by our immigrants.

How would the government communicate with them all? How would they communicate with one another?

Although Thomas Jefferson advised his son-in-law to learn French, German, and especially Spanish, Benjamin Franklin and John Adams discouraged the teaching of German and other languages in America. They, along with so many other influential Americans who followed, believed that the young American experiment required that immigrants leave their old worlds behind and adopt new lives as Americans, speaking a common language and sharing common ideals.

Indeed, many of these immigrants were happy to comply, as they were leaving because their home countries failed to deliver freedoms and opportunities that the American Dream promised. As Stanford professor Elizabeth Bernhardt observes in her analysis of the social context of language learning in America, our country was founded on a rejection of old-world thinking. “The very essence of America therefore contradicts the concept and goals of the teaching of foreign language and culture.”

The fact that English came to have dominion over the United States did not ensure peace in the years ahead. It was, perhaps, fortunate that our founding fathers didn’t live to see the American Civil War in which some one million Americans died, despite understanding the enemy’s language perfectly well.

But while the general infertility of American soil to language teaching was present from our beginnings as a nation, in the years that our nation was fighting the first world war, our fellow citizens plowed more salt into our fields. No one alive is old enough to remember the hangings of German-Americans, the German schools that were shuttered, the German newspapers that stopped printing, the German music, including Beethoven and Bach, that was struck from concert programs. Yet the results of that ethnic violence live with us still in the form of America’s paltry numbers of language enrollments (which are still in decline) and the marginalized role of American language teachers, who must advocate to avoid further reductions.

By world standards of bilingualism, the United States is a Language Lilliput. The nation that has received more immigrants than any other effectively put a gag order on those immigrants as the price of admission.

Did it have to go that way?

England was, of course, also at war with Germany. The war had already been shattering to Britain, piling up hideous numbers of dead in trench warfare. The British had their propaganda, aimed partly at the United States, exaggerating the atrocities of “the Huns.”

Theodore Roosevelt in Concord, NH, 1907. When war broke out in Europe, Roosevelt repudiated German-Americans and all forms of hyphenated Americans. (Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division.)

While I was researching this episode, my colleague Mim Harrison reminded me that during World War I, the British stopped calling their dogs German Shepherds and began calling them Alsatians. The British still call them by that name today. Yet, despite British antipathy to all things German, the British continued teaching German. According to Erik Kirschbaum, they thought it was important to understand the language of the enemy. Says Erik, “Why would you want to stop learning the language of the country you’re fighting against? It seems a bit strange, but it’s something distinctly American.”

Teddy Roosevelt railed against what he called the split loyalties of “hyphenated” Americans. “It is discouraging,” says Erik, “that Roosevelt knew German, yet was part of this big wave of hysteria to eradicate German from the United States.”

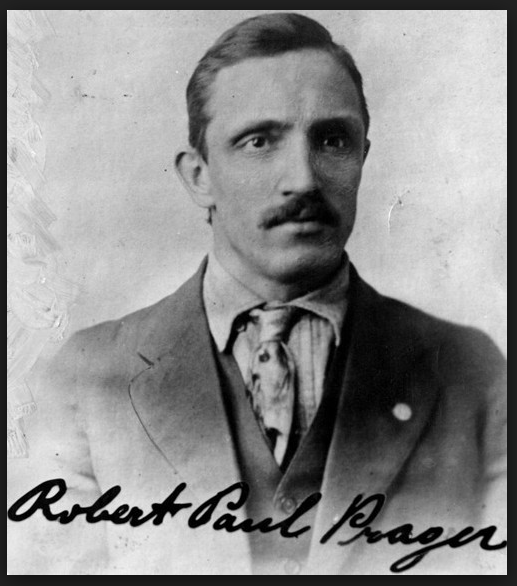

Robert Paul Prager, a German immigrant, was lynched by a mob near St. Louis at 12:30 am, April 5, 1918.

Our legacy: a national indifference to language learning

Having spent most of last year at Stanford, I can attest that the university has marvelous resources for learning world languages — for the relative few students who take advantage of them.

“We have a de facto one-year language requirement that students can place out of,” says Stanford Professor Russell Berman. “The Language Center does a great job, but I don’t think the institution as a whole is doing a great job at promoting second language acquisition. You don’t become fluent in a single year.” Says Russell, “Learning other languages is a crucial part of education both for their specific international payoff (whether that’s in the business side or in the culture side) but also because of the intellectual dimension associated with language learning. It’s a shame that it’s becoming so rare in the U.S.”

German-American exchanges today— enriching and lopsided

Today Erik leads an annual exchange of broadcast journalists between the U.S. and Germany. “We send about 30 Americans to Germany every year and about 30 Germans to the US.”

The exchange is funded by the RIAS Berlin Foundation. “I’m a big fan of exchanges; I know it changed my life,” Erik says. “I just get a big kick out of seeing young Americans and young Germans learning a lot about each other’s countries, going deep, going beyond the cliches.”

German broadcast journalists taking part in the RIAS Berlin Commission exchange program in the United States in October, 2017, visiting the WNBC studio in New York City, with co-host Michael Gargiulo (seated on the right). Erik Kirschbaum, the executive director, is standing fifth from the left.

While all the Germans chosen for the exchange speak English, most of the Americans do not speak German. “A few of them do, but I think if we made that a requirement, we wouldn’t have many candidates,” Erik says.

A similar story is told by Keith Cothrun, executive director of the American Association of Teachers of German. For some 20 years, Keith ran an annual exchange of his high school students in Arizona with students from Germany. Did his German students speak better English than his American students spoke German?

“Absolutely,” he says. “The German students started learning English in grade 5; the American students started learning German in grade 9. There are definitely advantages to having four years more of instruction before you go.”

Fortunately, a new generation of American students of German is rising. Kristin Gillett is a German teacher at Westford Academy public high school in Westford, Mass. “While you should not forget the past,” she says, “your history doesn’t necessarily define who you are now.”

Kristin Gillett (center) sees interest in German growing. She is shown here with some of her Westford Academy students in traditional outfits after their trip to Munich.

Hear the story

Hear author Erik Kirschbaum, professor Russell Berman and teacher Kristen Gillett in Episode 19 of America the Bilingual. We are a storytelling podcast reporting on the bilingual movement in America.

Listen on iTunes by clicking here: America the Bilingual by Steve Leveen on iTunes; on SoundCloud here; or wherever you listen to podcasts. Please subscribe and give us a review. It will help other people find the podcast. I’ll let you know about future episodes on Twitter as well.

We invite you to sign up at America the Bilingual for more reporting on the bilingual movement in America.

Sources and Credits:

The America the Bilingual podcast is part of the Lead with Languages campaign of ACTFL — The American Council on the Teaching of Foreign Languages.

This episode was written by me, Steve Leveen, and our producer Fernando Hernández, who also does our sound design and mixing. Our associate producer is Beckie Rankin, our brand and editorial director is Mim Harrison, and our graphic arts are created by Carlos Plaza Design Studio. Editorial consultant is Maja Thomas.

The book behind the New York Times Op-Ed piece is Burning Beethoven: The Eradication of German Culture in the United States during World War I by Erik Kirschbaum.

For more on the evolution of language education in America, see Elizabeth B. Bernhardt, “Sociohistorical Perspectives on Language Teaching in the Modern United States,” in Learning Foreign and Second Languages: Perspectives in Research and Scholarship, edited by Heidi Byrnes.

For how Theodore Roosevelt used his German and French while president, see Theodore Rex by Edmund Morris.

For how the British renamed German Shepherds, see The Great War and Modern Memory by Paul Fussell.

Special thanks to Professor Jeffrey Schneider of the German Studies Department of Vassar College, who provided an important background interview for this work.

Music in this episode with a Creative Commons Attribution Share Alike License (in order of appearance) by: Kevin Macleod, Jorge Mario Zuleta, Rafael Archangel, Francisco Penilla and Lee Rosevere.

Leave A Comment