Cratering Language Enrollments Reveal America’s Linguistic Divide

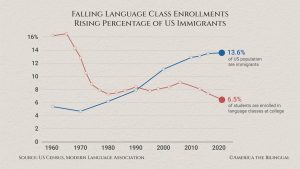

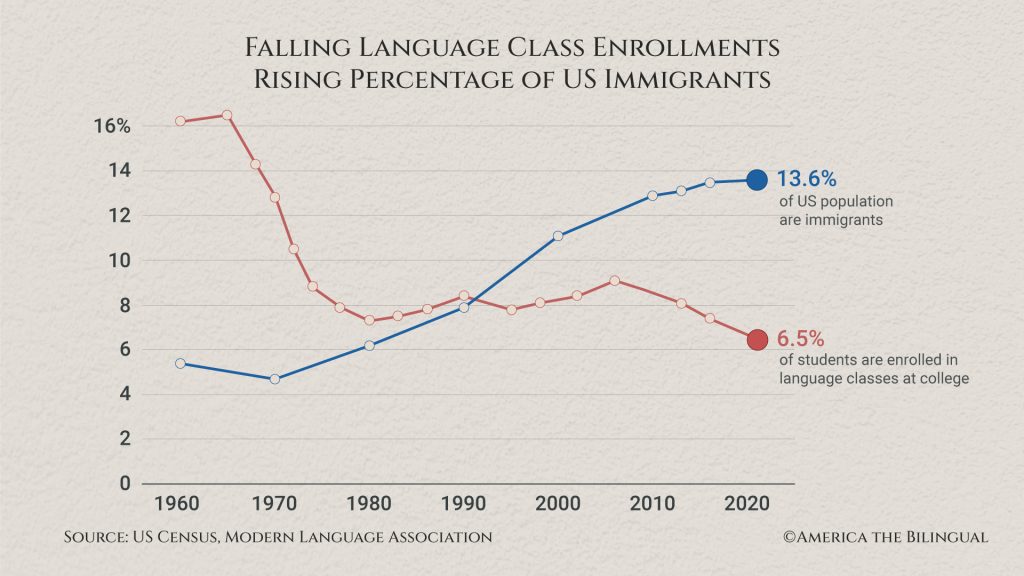

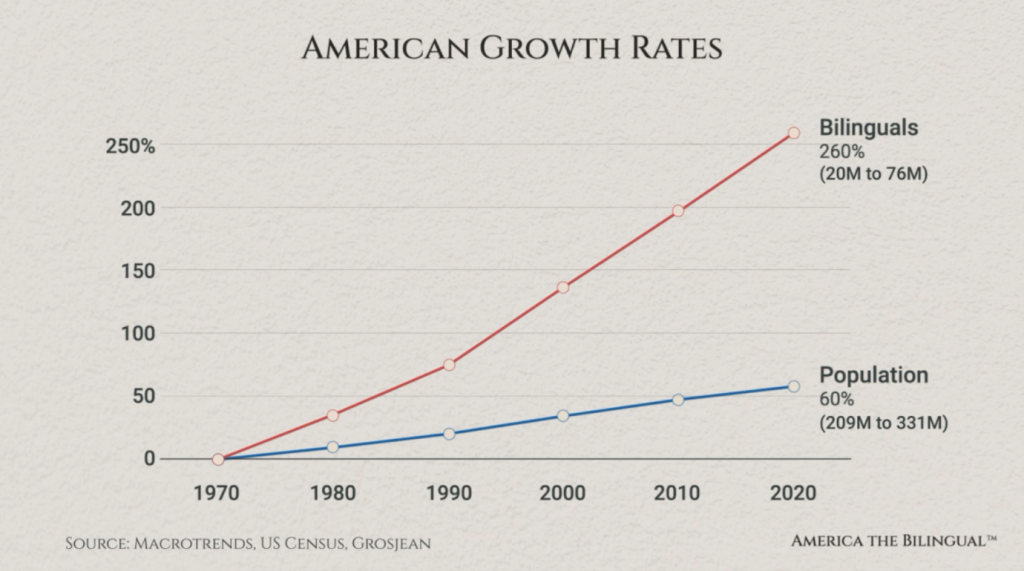

The Modern Language Association calls its recent survey of college language enrollments “staggering.” Enrollments in Spanish, French and especially German have cratered. In the dozen years between 2009 and 2021, language class enrollments dropped 29.3%, or by almost half a million students nationwide. It is the largest decline since the MLA began documenting language class enrollments back in the 1950s. Yet, in contrast, the number of American bilinguals has grown 260% in the last 50 years, from about 20 million in 1970 to more than 76 million today. How can both trends be true? The answer points to a growing divide between America’s linguistically rich and the country’s linguistically poor.

Rich kids, then and now

“Bilingualism has always been a gift the rich have given to their children,” observes Guadalupe Valdés, a professor emerita in Stanford’s Graduate School of Education. This was, and still is, done with the help of nannies, tutors, private schools, travel and study abroad. What’s different today is that bilingualism is now a recognized gift that immigrant parents are giving to their children, too.

Even though recent immigrants may not have great material wealth, they are a significant group of the linguistically rich. And immigrants are a primary reason for the 260% rise in American bilingualism.

This wasn’t always the case.

Before the 1960s, there was little incentive for immigrant parents to pass on their home language to their children. Jobs that immigrant parents held as aspirational for their children were mainly English-speaking jobs. Travel back to the home country, where their kids might speak their Italian or Polish with their cousins, meant booking passage on a steamship, for an expensive, week-long voyage that was out of reach for most parents. And the main means for communication back to the home country before the 1960s were handwritten letters. These practical factors combined with peer pressure to be as American as the Joneses next door helped make language loss in the US far more rapid than was typically the case for immigrants in other countries.

While the pressure on immigrants to speak English like a native has not let up, since 1960, the rapid advance of technology has dramatically changed the practicality and usefulness of passing on home languages.

As businesses became more international, so did jobs, giving advantages to employees who could communicate in English plus another language. With airliners, travel back to the home country became relatively cheap and fast. Phone calls to family back in the home country got cheaper and cheaper, and then became unnecessary with today’s instant video communication. If this wasn’t enough of an incentive for parents to pass on their heritage language, or at least try to, social science did a 180 on bilingualism, from viewing it as a negative for education prior to the 1960s, to viewing it as a strong positive. American children fortunate enough to attend dual-language schools, where they are taught half in English and half in another language, outscore their monolingual English peers not only overall, but even in English.

Language teachers also recognize that students who come to class already speaking a heritage language have different educational needs. Typically they need less work on speaking and listening, but more work on reading and writing. Heritage language teaching is now a speciality that has been growing rapidly, giving more advantages to the children of immigrants.

The result of all this is that more American immigrant kids now gain the gift of bilingualism that only their rich classmates gained before. This is why approximately 23% of the American population is now bilingual. Unfortunately, the majority of American kids are growing up in English-speaking homes and remain marooned in monolingualism. The resulting linguistic divide harms America’s global competitiveness and the millions of young Americans destined to stand out in the world as the last of the monolinguals.

Colleges asleep at the switch?

While the most recent declines in college language enrollments are the sharpest yet, gradual declines have been going on for decades. Walking around campuses back in 1965, the chance of bumping into a student who was taking a language class was 1 in 6. In 2021, you’d have to bump into 15 students before finding one taking a language class. Long-term studies like this one are rare, so kudos to the MLA for doing the hard work of collecting and reporting the data from thousands of colleges.

To understand the full ramifications of the data, you have to read beyond the first pages.

In the most recent 12 years of data (2009–2021), language enrollment declines have been steeper in community colleges (-44.3%) than in four-year colleges and universities (-24.8%), and deeper in public universities (-17.5% since 2016) than in private ones (-7.8% since 2016). These disparities show how middle-class students who grow up in English-speaking homes are finding fewer opportunities in school to get traction with a second language.

Actually, our English monoculture is choking out language classes well before college. According to an American Academy of Arts & Sciences report, only 15% of public elementary schools offer language classes of any kind, while more than 50% of private schools do.

Part of the reason for the declines is a public relations problem. Despite negative experiences that many older Americans may have had in high school, many language classes have improved over the years. They are generally more effective than in classrooms past, and most take advantage of modern technology. Today’s college classes provide nothing less than a solid foundation…and nothing more. Such foundations can be invaluable to students, but students may become discouraged because classes alone can’t deliver the thousands of hours of actual use that acquiring a language requires. It’s not just a PR problem, however. Universities have been slow to adapt to what their students want and need: language skills that connect to real-world skills in a variety of careers.

Traditionally, advanced language classes meant studying literature. While it’s rewarding to read Flaubert and Cervantes in their original languages, there are vanishingly few jobs available for professors of comparative literature. In contrast, the job horizon is bright for graduates who are doubly qualified—in their professional skills, plus in a language beyond English. When colleges do offer such applied language training in the form of language for specific purposes (LSP), enrollment grows. For evidence, consider American Sign Language.

ASL has been taught for a very long time, but only later in the 20th century did it gain recognition as a full-fledged language. When the MLA began counting ASL enrollments in 1990, it reported only 1,602 nationwide. Since then, enrollments have surged, overtaking German to become the third most studied language in American colleges in 2013. Since 2009 the number of ASL programs in American four-year undergraduate institutions grew from 353 to 487 in 2021, with total enrollments exceeding 100,000. Why? One simple reason: jobs.

Of course, students are also drawn to the beauty of ASL and to caring for others, but the driver has been federal laws requiring meaningful access for the Deaf community. That’s why it is now customary to see ASL interpreters working off to the side during speeches by public officials and others.

The promise of richer career choices has also fueled growth in other language courses targeting the professions, such as Spanish for health care. Emory & Henry College, a small liberal-arts college in Virginia, can boast of having more than a quarter of all its students studying Spanish. What’s their secret? The college offers a practical, two-semester course in Medical Spanish. Reports the MLA, “The success with Medical Spanish has prompted interest in doing something similar for business majors and for those entering the field of human services.”

At the University of Chicago, multiple language programs are conducting research to define the knowledge, skills, and abilities necessary to function in different professional contexts, including law, public policy, social work, and business economics.

Language departments have traditionally been part of the humanities, and they certainly belong there, but languages are also practical skills that belong equally with the professions.

Are incoming college students more skilled than their parents were?

Unfortunately, we don’t have any nationwide measure of the language skills of entering college students, but there are reasons to believe that their skills have gone up in recent decades.

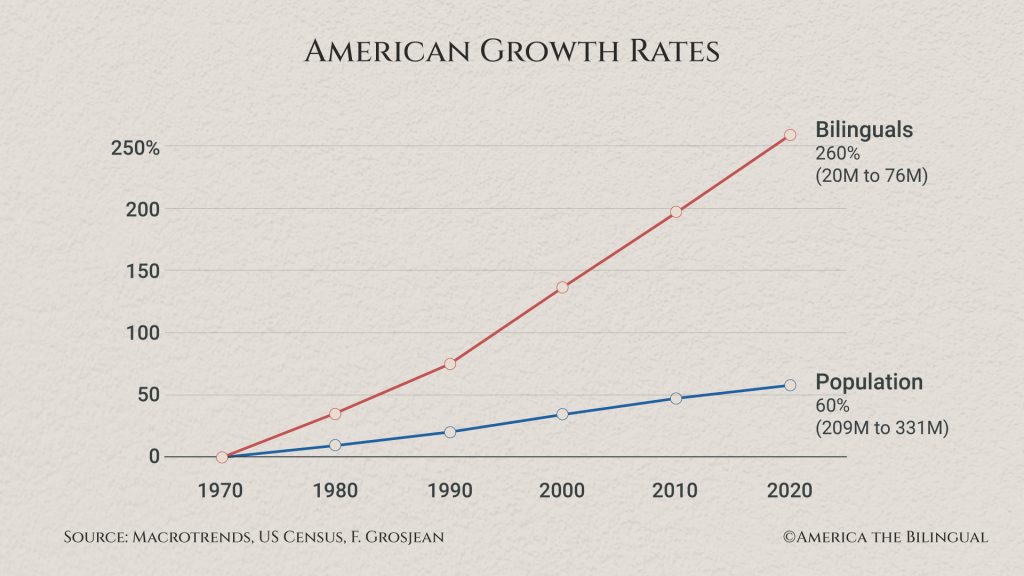

Along with record numbers of immigrants since the 1970s, many of them speaking their heritage languages at home, the number of American dual-language programs in schools has gone from single digits in the early 1970s to more than 3,600 programs today.

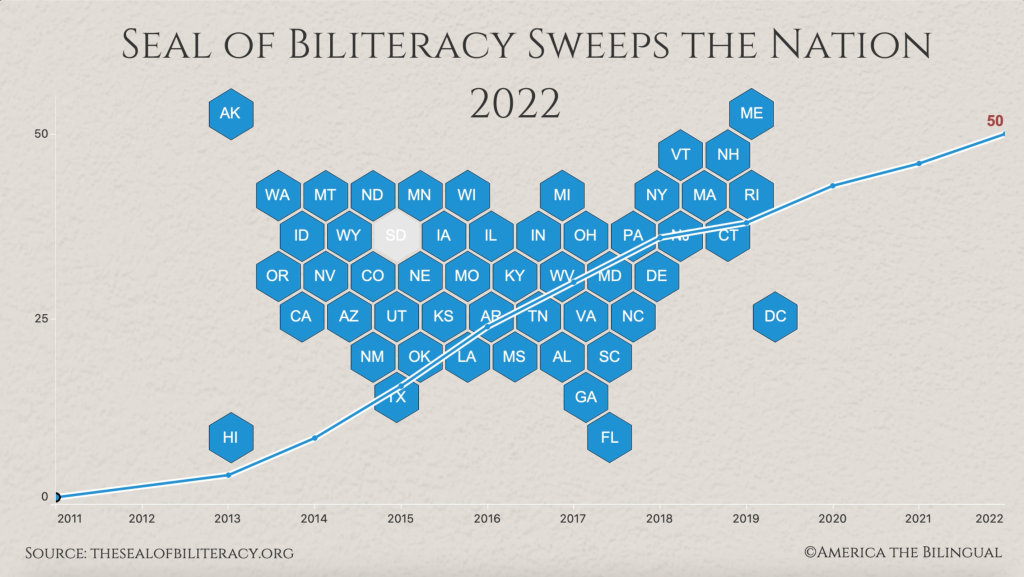

The State Seal of Biliteracy, which high school students can earn by demonstrating oral and written proficiency in two languages, started in California in 2011 and has spread rapidly since then to 49 states and the District of Columbia. Adding to the state seals is a Global Seal of Biliteracy, which has grown from zero to over 30,000 over these years.

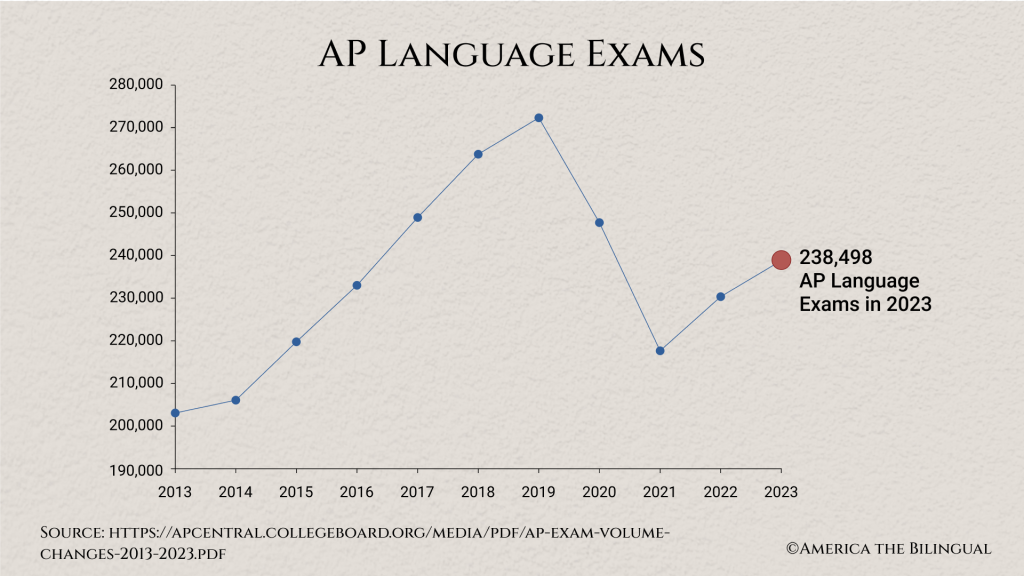

High school students are also demonstrating their language skills by taking Advanced Placement exams, which have grown 42% since 2009. In 2022, nearly a quarter of a million students took language AP exams in Spanish, French, German, Italian, Chinese and Japanese. Of those taking the Spanish exam, more than 80% scored 3 and above (with 5 being the best).

More than 60% of students taking the AP language exams are heritage speakers, providing another avenue for them to demonstrate reading and writing skills in non-English languages that before 1960 were likely never developed.

While you are less likely to bump into a college student taking a language class today than in decades past, you are more likely to run into a student who was born overseas. Forward-thinking college leaders are challenging these and all students to write and present at the college level in more than just English, giving them practical training for the real world. Sure, go ahead and major in computer science, but minor in German or Chinese or Korean, and then you’ll stand out from the crowd.

Universities that are serious about helping their language students direct them to internships and jobs in the burgeoning language services industry. It’s a multibillion-dollar industry that helps global organizations localize their services around the world. These companies help Netflix provide dozens of audio tracks and subtitles in other languages, and Apple its iPhone instructions in scores of languages.

The ALC Bridge, produced by the Association of Language Companies, helps students find jobs in the industry. More opportunities can be found at the American Translators Association and the rapidly growing Women in Localization.

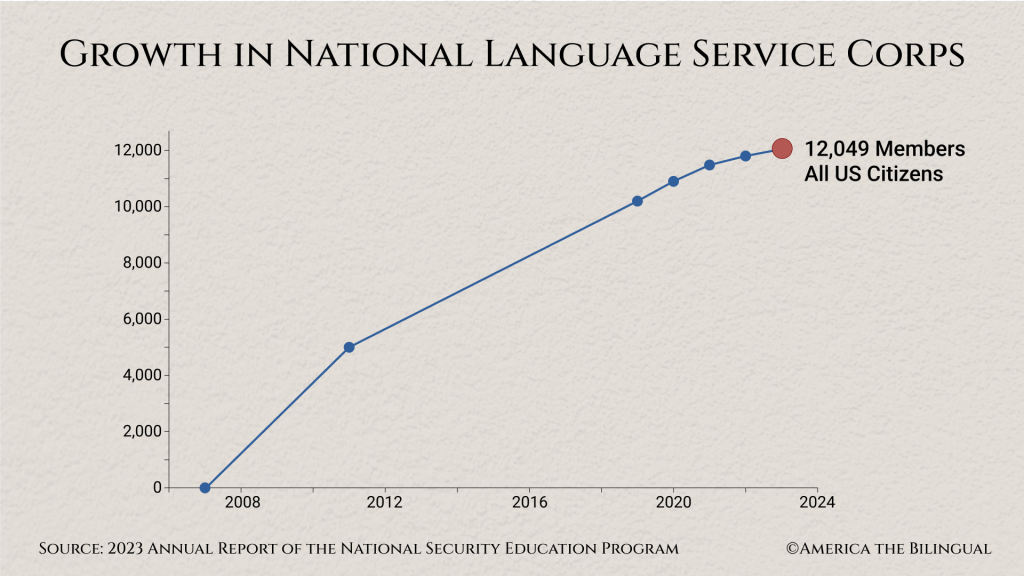

As for public service, a search at USAJOBS.GOV for languages such as Mandarin, Korean, Farsi, Arabic, Russian and many others will yield a surprising array of openings. And our National Language Service Corps, a little-known reserve force of skilled linguists ready to assist federal government agencies, has grown its membership dramatically.

Last of the monolinguals

But the decline in language class enrollment is not all, or even mainly, the fault of our colleges.

A large part of our national challenge has to do with social norms. Most American kids grow up thinking monolingualism is perfectly normal, because it is perfectly normal in their lives. Yet the reality is that most humans are already bilingual, and bilingualism is growing both in the US and worldwide.

Then there are two damaging but widespread beliefs, based on half-truths.

First is the belief that “the whole world speaks English.” It’s true that if you want to be a tourist and buy things (and there’s nothing wrong with either), you can do that in English in most of the highly traveled places in the world. But this isn’t at all true for professional work. If you want to work professionally in an international setting—in practically any field—knowing the language of your customers, competitors and colleagues is a ticket to success.

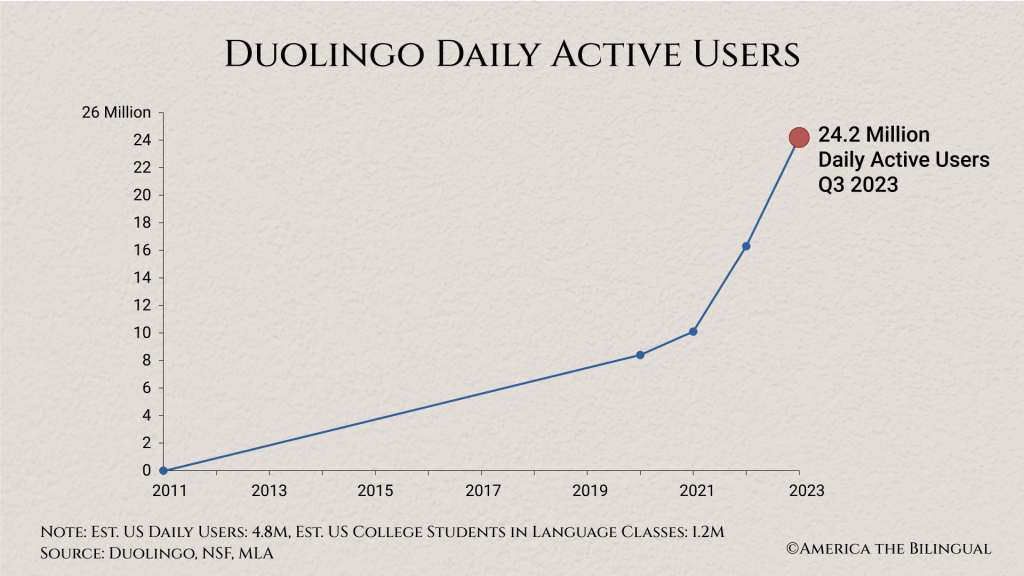

The second half-truth is the idea that computers will make language learning obsolete. It is true that AI driven machine translation is already helping to create millions of documents, websites and movie subtitles. But equally powerful is the use of AI software for human learning, making language learning more enjoyable and effective than ever. Duolingo is a leading company among hundreds that are ushering in a golden age of language learning.

What used to be called the language lab on campuses now exists in the pocket of every student. Using technology, together with up-to-date classroom teaching, can achieve results that only rich kids could achieve in the last century.

Fortunately, many young Americans from coast to coast are setting these half-truths aside and taking advantage of both technology and classroom teaching to help gain language skills. But this isn’t happening evenly, or everywhere.

The growing divide between our American linguistic haves and have-nots poses a danger to the individuals left behind, and to our nation for our global competitiveness. But the solution is clear: We must attack the linguistic divide using advanced technology and enlightened classroom teaching. Providing meaningful language training to our least privileged Americans is the most effective way to boost American bilingualism overall. In the end, it’s simple: If you want to understand our world, you have to listen to it.

– Steve Leveen

You can book Steve for many different audiences

You can book Steve for many different audiences

First, know that she has one of those glorious English accents (or what all of us who are not English would call an accent), which makes her a natural for the audio book narration that she does. Although U.S. born, Caroline grew up in England and studied literature at the University of Warwick (fyi for American ears: that second “w” is silent).

First, know that she has one of those glorious English accents (or what all of us who are not English would call an accent), which makes her a natural for the audio book narration that she does. Although U.S. born, Caroline grew up in England and studied literature at the University of Warwick (fyi for American ears: that second “w” is silent).

Leave A Comment