30. A New Generation of Cherokee Speakers Rises

Among the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians in North Carolina, there are fewer than 200 first-language speakers of Cherokee. In Episode 30 of America the Bilingual, you’ll hear from people, both Cherokee and non-Cherokee, who are finding ways to embed the Cherokee language in classrooms and music, giving rise to a new generation of Cherokee speakers in the process.

But is it too late?

And how did it get to this point?

First land, then language

When gold was discovered in Georgia in 1829, the news did not bode well for the Cherokee people, whose ancestral homeland encompassed this region. President Andrew Jackson, ignoring the decision of a U.S. Supreme Court judge that his “Indian Removal Act” was unconstitutional, forced the Cherokees on a 1,000-mile march into Oklahoma—the infamous Trail of Tears.

Later in that century and through the middle of the 20th century, having already lost their land, Cherokees found themselves in danger of also losing their language—this among a people whose literacy rate in the 1800s had eclipsed that of the European-American settlers. [See the story “Talking Leaves” on the articles page of this site.]

But the U.S. government prohibited Cherokee to be spoken in schools. Eventually, that meant it wasn’t spoken at home, either.

200 and counting—upward

That’s led to there being only about 200 Cherokees in the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians for whom their heritage language is their first language.

But today, these Cherokee people, who live in western North Carolina, are restoring what was theirs. In their schools, students are learning the Cherokee language.

Cherokee is also one of the languages that the State of North Carolina offers in its expansive dual-language immersion program for all public schools. And in the New Kituwah Language Academy in Cherokee, North Carolina, the only language you’ll hear is Cherokee. “English,” announces a sign at the entrance, “Stops Here.”

Voices in the podcast

What doesn’t stop is the resolve of the people Steve interviewed for this episode. His visit to North Carolina this summer coincided with Cherokee teachers from the Cherokee Nation in Oklahoma meeting with teachers from the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians.

The comments you’re about to read are in addition to what you’ll hear in the podcast.

Here’s Renissa McLaughlin, Director of Youth and Adult Education for the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians in North Carolina:

“When you tell someone that their language is unimportant, you’re taking it away from them. It’s an emotional attack. Our speakers have an emotional attachment to the language that they held at bay for all these years when the boarding schools were saying, ‘you’re going to learn English.’

“When you ask, why is it important for children to learn the language—it’s not just about the child. It’s about the tribe. And being able to bring that happiness back.”

Renissa McLaughlin with Adult Language Coordinator Micah Swimmer, on the grand marshal float of the New Kituwah Academy’s 2016 fall fair.

This is Kathy Sierra, Director of the Cherokee National Youth Choir in Oklahoma and a Cherokee language teacher:

“I would put my grandchildren anywhere so they can learn Cherokee. Thank God my children agreed with me.”

Kathy Sierra, who uses songs to help children learn the Cherokee language and history.

And Sara Snyder, Director of the Cherokee Language Program at Western Carolina University:

“The language carries so much information about culture and history. Even today, we’ve been learning about what these place names mean, and that ties to the history of that place. Without the language, we have no way of decoding that information, or having that information anymore. Having a living language means that you can still access that information in daily life.”

Sara Snyder, who explores how music can be used in endangered-language programs.

Embedded in heritage languages: humanity

Hartwell Francis is the Education Curriculum Developer for the Kituwah Preservation and Education Program. He will tell you that studies conducted in Canada, a land of many First Nation indigenous peoples, have found that children who know their heritage language are less likely to commit suicide in later years than those who don’t.

“That suggests there’s a close connection between language and identity,” Hartwell says. Knowing Cherokee helps young Cherokee students have a positive self-identity. And that, he says, means that…

“You don’t have to express your identity in a negative way by rejecting the school system because ‘I’m a Cherokee person and I’m not going to go through that white-man schooling system.’ You can succeed academically.”

Sequoyah’s syllabary and Yankee Doodle’s song

Although no Native people in North America possessed a written language when the Europeans first arrived, the Cherokees have had one since 1821 (which led to that high literacy rate).

A Cherokee scholar named Sequoyah created it. He used a syllabary rather than an alphabet as the basis of the language—syllables, in other words, instead of single letters. [See the syllabary in the “Talking Leaves” article.]

In somewhat of an ironic twist, given what had occurred in 1829, Sam Houston is said to have told Sequoya that “Your invention of the alphabet [sic] is worth more to your people than two bags full of gold in the hands of every Cherokee.”

Sequoyah, as depicted on the 2017 commemorative Native American $1 coin of the U.S. Mint.

In her interview, Kathy Sierra told Steve of Sequoyah’s recent induction into the Oklahoma Hall of Fame. It is thanks to Sequoyah, she pointed out, that it’s still possible to learn to read and write Cherokee, even if you have no speaker to teach you.

But Sequoyah is actually helping the children who are now learning to speak Cherokee as well. Kathy was involved in repurposing the tune of “Yankee Doodle Dandy” with an all-Cherokee version that celebrates Sequoyah’s single-handed accomplishment.

“The kids pick up all the Cherokee words just like that,” she said of the tune.

Charlotte’s Web, in Cherokee

Students at the New Kituwah Language Academy learn how to both speak and read Cherokee. That’s led to the need for more books written in Cherokee for the youngsters.

The students now have a cherished American classic to enjoy, Charlotte’s Web by E.B. White (1899-1985). Myrtle Driver, who is Cherokee, devoted three years to the translation.

“She was so deep into that book,” said Sara Snyder. “The way she describes things gives a real Cherokee perspective and Cherokee consciousness. It makes it Cherokee in a way that’s really beautiful.”

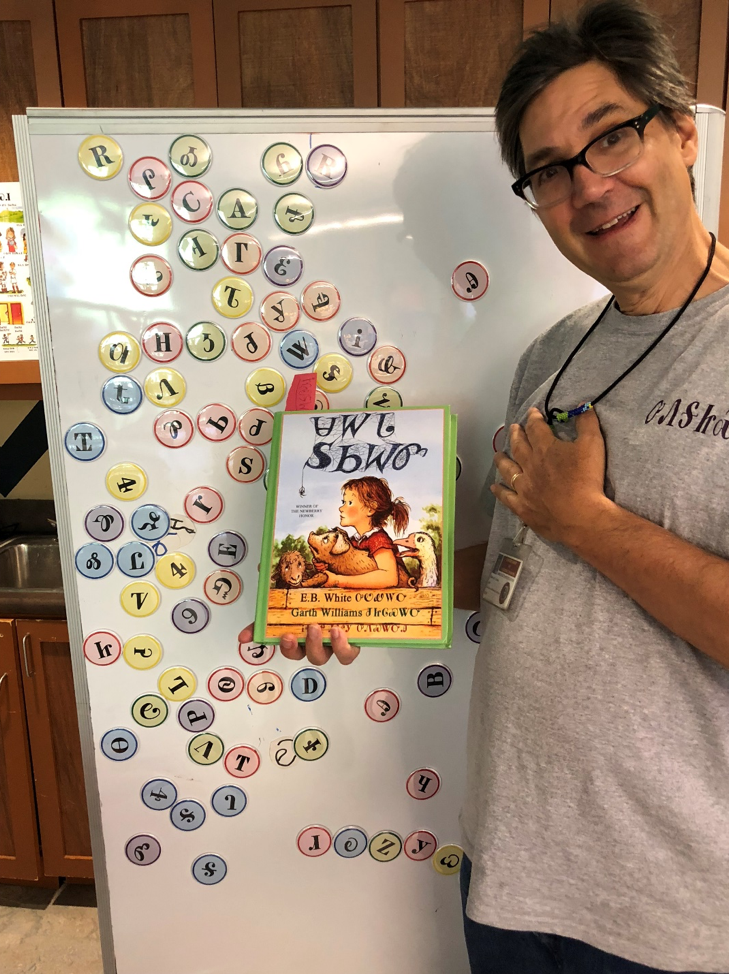

Hartwell Francis holds the Cherokee version of Charlotte’s Web, translated by Myrtle Driver.

The granddaughter of E.B. White, Martha White, is the literary executor of the author’s estate.

“I remember when I gave permission for the Cherokee translation, thinking how surprised and pleased my grandfather would be to think that Charlotte and her friends could help preserve a language,” Martha relayed to us by email. “My grandfather was always ‘a word man,’ trying to voice what needs to be said. He gave voice to the barnyard, and he gave Louie the Trumpeter Swan his voice. Now he’s helping to do the same for the Cherokee nation.”

Myrtle Driver is Renissa McLaughlin’s mother. Ask Renissa if it’s too late to save the Cherokee language, and she will tell you.

“It’s not too late. As long as there are still people that can speak the language, there’s still opportunity for the younger population.”

Hear the story

Hear more about the resurgence of the Cherokee language in Episode 30 of the America the Bilingual podcast, “A New Generation of Cherokee Speakers Rises.” Listen on iTunes by clicking here: America the Bilingual by Steve Leveen on iTunes. Or on SoundCloud here. Steve comments on Twitter as well.

Credits

The America the Bilingual podcast is part of the campaign of ACTFL—The American Council on the Teaching of Foreign Languages.

This episode was written by Mim Harrison, who also wrote these notes, and produced by Fernando Hernández, who does the sound design and mixing as well. The associate producer is Beckie Rankin. Graphic arts are created by Carlos Plaza Design Studio. Meet the team—including our bark-lingual mascot, Chet—here.

Support for the America the Bilingual project comes from the Levenger Foundation.

Music in this episode, “Quasi Motion” by Kevin MacLeod, was used with a Creative Commons Attribution License. Our thanks to Epidemic Sound for helping us make beautiful music together.

You can book Steve for many different audiences

You can book Steve for many different audiences

First, know that she has one of those glorious English accents (or what all of us who are not English would call an accent), which makes her a natural for the audio book narration that she does. Although U.S. born, Caroline grew up in England and studied literature at the University of Warwick (fyi for American ears: that second “w” is silent).

First, know that she has one of those glorious English accents (or what all of us who are not English would call an accent), which makes her a natural for the audio book narration that she does. Although U.S. born, Caroline grew up in England and studied literature at the University of Warwick (fyi for American ears: that second “w” is silent).