27. How to Learn a Language Without Studying It

When people find out I’m learning Spanish, they frequently ask me, “How are you doing it?” It’s an obvious question. But over the years I’ve discovered that it’s not the best question. A better one is, “What are you doing with your language?” For when you can answer that question, you have discovered a place, or places, where your adopted language can live in your life. That, as we’ll hear in this episode, makes all the difference.

The way we acquire language

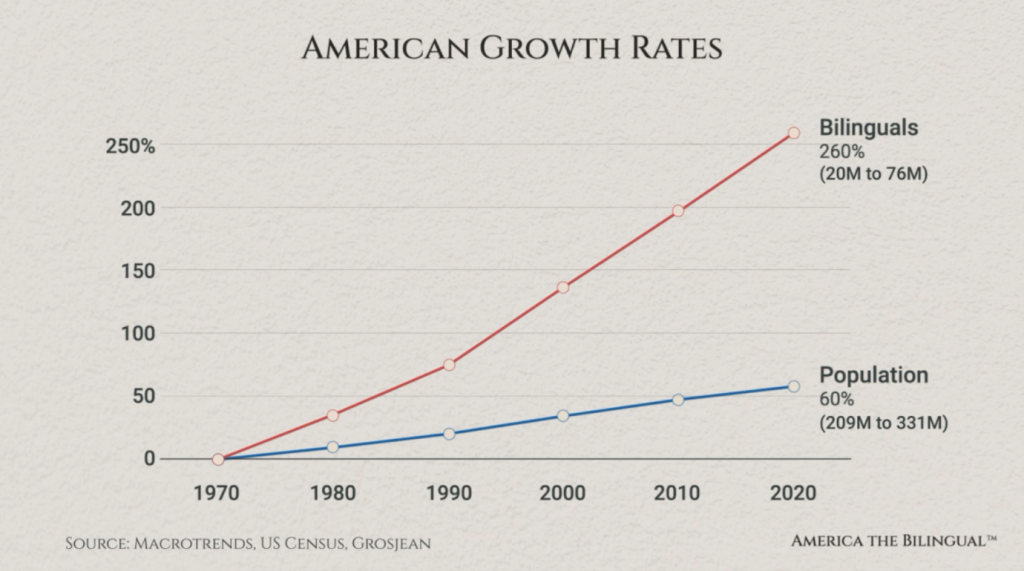

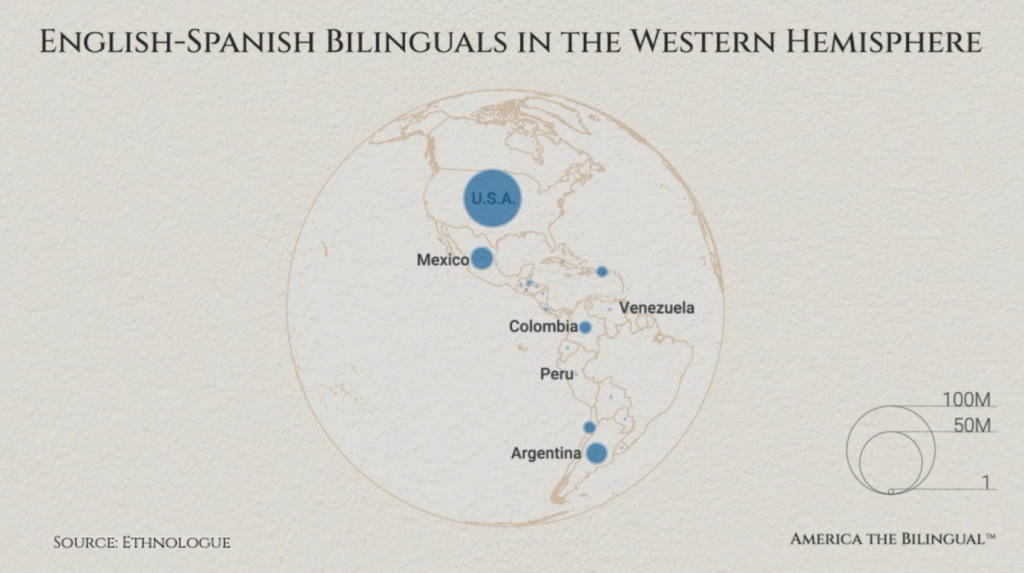

About 70 percent of Americans speak only English, according to U.S. Census and private surveys. The 30 percent who do speak a second language are mostly immigrants, or the children of immigrants. Few Americans who grow up with only English spoken at home manage to become bilingual.

When I ask my fellow monolinguals about their language biographies, they frequently tell me a story that sounds like this: “I took four years of French and can barely utter a sentence.” They tend to blame themselves, and also “the way we teach languages.”

The language teachers I’ve interviewed are quick to admit that language classes in the past were frequently ineffective—filled with “drill-and-kill,” too much focus on grammar, and lacking in instruction that could actually help students function in the language. It’s also true that language classes have improved greatly in recent decades. (We’ll be reporting on that in a future episode, “Not Your Uncle’s Language Class.”)

Much of the problem, however, lies in the unrealistic expectations we seem to have for what can be accomplished in a classroom.

“As soon as you talk to people about learning a language, they think you have to take a class,” says Professor Guadalupe Valdez at Stanford University. Classes aren’t bad, she says, except that they can take us only so far.

Part of the shortfall is simply the hours. Four years of classroom French will amount to a few hundred hours of actually using the language, whereas we need a few thousand hours to begin to be conversational. But there’s more to it than just hours.

“What happens in instructed language acquisition,” says Guadalupe, “is that the learners always outnumber the fluent speakers.” While learners can practice the language, “the affordances for hearing genuine language are limited.”

Likewise, she says, we have unrealistic expectations about software. “We have many things online now, like Duolingo or Rosetta Stone, any number of those things that are out there, and you’re encouraged to try to work all by yourself with bits and pieces of language. And, indeed, you will acquire some language, but working with bits and pieces of language takes a very long time, if you never have the occasion to use the language.”

Our unrealistic expectations of how far classrooms and software can take us belie what we can actually observe in the world, says Guadalupe “You can, in fact, acquire a language if you’re dropped into the world where you have to survive. That is the way language is acquired naturally—the way you acquire a first language—by being surrounded by fluent speakers who speak to you and act as though you understand.”

I asked Guadalupe if America is doomed to remain a majority monolingual nation. “My opinion would be that we likely are, as long as we continue to primarily, or exclusively, teach languages as subjects rather than using those languages as mediums of instruction.

“Language is acquired in use from individuals who are communicated with, by people who are expecting you to understand, wanting you to understand and inviting you to understand,” Guadalupe says.

So how do we find those real-life situations where we can be surrounded by people expecting, wanting and inviting us to understand? The answer depends on what you will use your language for.

Robin Loving Uses Her Spanish to Help Mexican Girls

In Episode 16, “Bless the Late-Blooming Bilinguals,” we heard from Texan Robin Loving, who moved to San Miguel de Allende, Mexico. She had studied Spanish in classes while in school in the United States and continued studying in Mexico with a private tutor. But her real learning, she says, began when she started working in a girls’ school.

Robin said the American expats living in San Miguel who really improve their Spanish are the ones who do things in the language.

“Art classes, dance classes and cooking classes—those are the three most popular, and those are taught in Spanish,” says Robin.

Robin describes taking a cooking class from a Mexican woman. “She’ll take the Americans to the market and explain what they’re buying, and then take them to her kitchen and actually show them the implements that she’s using to make these things, and then use the terms—for instance, a comal, or griddle.”

It’s real life, says Robin. “You can learn on the job. You don’t have to just study in an abstract way—it’s much more applicable.”

Susan Golden Cooks With Italian

Susan Golden, a visiting scholar at Stanford, says learning Hebrew and Italian on the job was “joyful.”

On-the-job learning is just what Susan Golden did at age 16 when she went to live on a kibbutz in Israel. That summer, she was enrolled in the Israel Ulpan program of class instruction in Hebrew, but, says Susan, “where I really learned to speak was when I was assigned to the children’s houses. The three-year-olds spoke at a rate and with a vocabulary that I could understand, and they enabled me to really learn the language. It was a joyful experience.”

Decades later, when Susan had a few months off between jobs, she knew she didn’t want to take conventional language classes to learn Italian. Based on her rewarding experience in Israel, Susan decided she would go to Italy to learn cooking through the medium of Italian. “While I wasn’t there long enough to become fluent, it was another joyful experience.” Susan’s Italian lives on through the recipes she learned in Florence and continues to cook for her family.

Brad Schmier Hones His Scientific Knowledge in Spanish

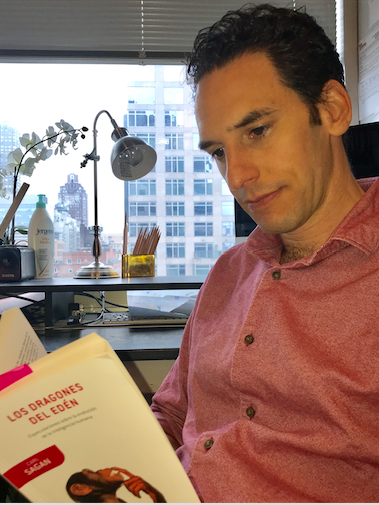

Brad Schmier reads a popular book on science in his adopted language of Spanish. “Reading in Spanish helps my hearing and speaking, too.”

Brad Schmier is a molecular biologist working at Memorial Sloan Kettering in New York City. In his thirties, building his career, raising a family, Brad found it difficult to continue learning Spanish. The advances he had made while a graduate student at the University of Miami were starting to fade. Finally, he found an answer to the question, “What will you do with your language?”

He combined his love of books, his desire to learn about the history of cancer and his love of Spanish, reading two bestselling books about the history of cancer in Spanish. Now he’s continuing to read popular, bestselling scientific books as well as biographies in Spanish. “I find that reading in Spanish helps my hearing and speaking,” he says. He also likes to remember phrases. One of his favorites in from Walter Isaacson’s biography of Steve Jobs: El viaje es la recompensa. (The journey is the reward.)

How to think about language classes

Language classes can be “helpful as a mental organization tool” before heading out on real-life experiences, says America the Bilingual Associate Producer Beckie Rankin. But when classes are followed by immersion experiences, that’s when learning accelerates. “I see this every year: my students who go to Europe for two weeks on my exchange program outperform their peers who do not immerse themselves in the culture.”

Beckie says we should think of language classes as starting points, not end points. “The greatest gift you can give your language teacher is to visit the countries they taught you about, make mistakes, laugh, and learn more about the people you encounter.” Beckie, who teaches French at Lexington High School, outside of Boston, says there are many French-speaking countries to visit and that French can open students to much of the world.

“None of us teach language just to hear grammatically perfect sentences—we teach language and culture to open our students’ eyes to other ways of being.”

My own answers

What am I doing with my Spanish? Where will it live in my life?

I’m still answering those questions myself. So far, my Spanish lives in the news I hear weekly on “News in Slow Spanish” and on Voice of America in Spanish. It lives in the movies and Netflix series I watch for enjoyment, with my patient wife. And, as with Brad Schmier, my Spanish lives in my reading, although this has been a rocky path for me.

First I got children’s books, but they were too simple. Reading them became just a language exercise. It wasn’t terrible, but I wasn’t feeling the pull of a good book that would get me focused on the story and not on the Spanish.

Then I went too literary. I went for prize winners like Gabriel García Márquez and Carlos Fuentes. But I found those authors are hard for me to read in English, let alone in Spanish. My reading was super slow and again, it became more an exercise rather than enjoyable reading.

I hope that someday my Spanish will be good enough to read serious literature for enjoyment. For now, I’ll enjoy gripping bestsellers and capture the double enjoyment of reading them in my beloved adopted language of Spanish.

Finally, I decided to just go for a page-turning novel. I bought a bestseller by Julia Navarro titled Dime Quien Soy, which means “Tell Me Who I Am.” It’s a story of a woman named Amelia who lives through the Spanish Civil War, Stalin’s Russia, Hitler’s Germany and finally, the fall of the Berlin Wall. Navarro is an artful storyteller and the plot is straightforward, so the book could work its magic on me. It was the first time I was reading for pleasure in Spanish, and it was glorious.

My whole life, I have rarely allowed myself the guilty pleasure of reading page-turning bestsellers. I felt I should be reading serious literature. But now I’m giving into the pleasure of a summer read because I know it’s what my Spanish life needs.

So I ask you, dear reader and dear listener: What will you do with your language? Where will it live in your life?

HEAR THE STORY

Hear more of the story in Episode 27 of the America the Bilingual podcast, “How to Learn a Language Without Studying It.” Listen on iTunes by clicking here: America the Bilingual by Steve Leveen on iTunes. Or on SoundCloud here. I’ll let you know about future episodes on Twitter as well.

Sources, Credits and Additional Thanks

Special thanks to my friend Jim Hall for arranging that unexpected game on the polo field that you’ll hear about in the podcast. Oddly, it was that experience on horseback that got me thinking about the way we learn languages.

The America the Bilingual podcast is part of the Lead with Languages campaign of ACTFL — The American Council on the Teaching of Foreign Languages.

This episode was written by me, Steve Leveen. Our producer is Fernando Hernández, who also does our sound design and mixing, and our associate producer is Beckie Rankin. Our brand and editorial director is Mim Harrison. Graphic arts are created by Carlos Plaza Design Studio.

Support for the America the Bilingual project comes from the Levenger Foundation.

Music in this episode, “Quasi Motion” by Kevin MacLeod, was used with a Creative Commons Attribution License. Our thanks to Epidemic Sound for helping us make beautiful music together.

You can book Steve for many different audiences

You can book Steve for many different audiences

First, know that she has one of those glorious English accents (or what all of us who are not English would call an accent), which makes her a natural for the audio book narration that she does. Although U.S. born, Caroline grew up in England and studied literature at the University of Warwick (fyi for American ears: that second “w” is silent).

First, know that she has one of those glorious English accents (or what all of us who are not English would call an accent), which makes her a natural for the audio book narration that she does. Although U.S. born, Caroline grew up in England and studied literature at the University of Warwick (fyi for American ears: that second “w” is silent).

Leave A Comment